Everyone should feel safe at work. Increasingly, workers around the world are calling for more ethical and inclusive leadership and working environments, and concepts like empathy, cultural awareness, emotional intelligence, and psychological safety all play a part. We have Amy Edmonson, Professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School, to thank for the term ‘psychological safety,’ which she defines as a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.

Consider what “speaking up” means to you, and how you would do so in your current role. Perhaps you’re imagining offering a new creative idea during a team meeting, or maybe you are in a one-on-one conversation with your manager. Maybe you can’t see yourself speaking up face-to-face and would rather send an email. Perhaps you can’t imagine any scenario in which “speaking up” doesn’t result in backlash.

Factors such as your relationship with your manager, years of experience, and preferred work style all contribute to how and when you might choose to “speak up.” Perhaps one of the biggest influences is cultural background.

Cultures have dramatically different work style norms. The GlobeSmart®Profile provides a high-level overview of these cultural differences, which can help us start to understand one another’s work style preferences.

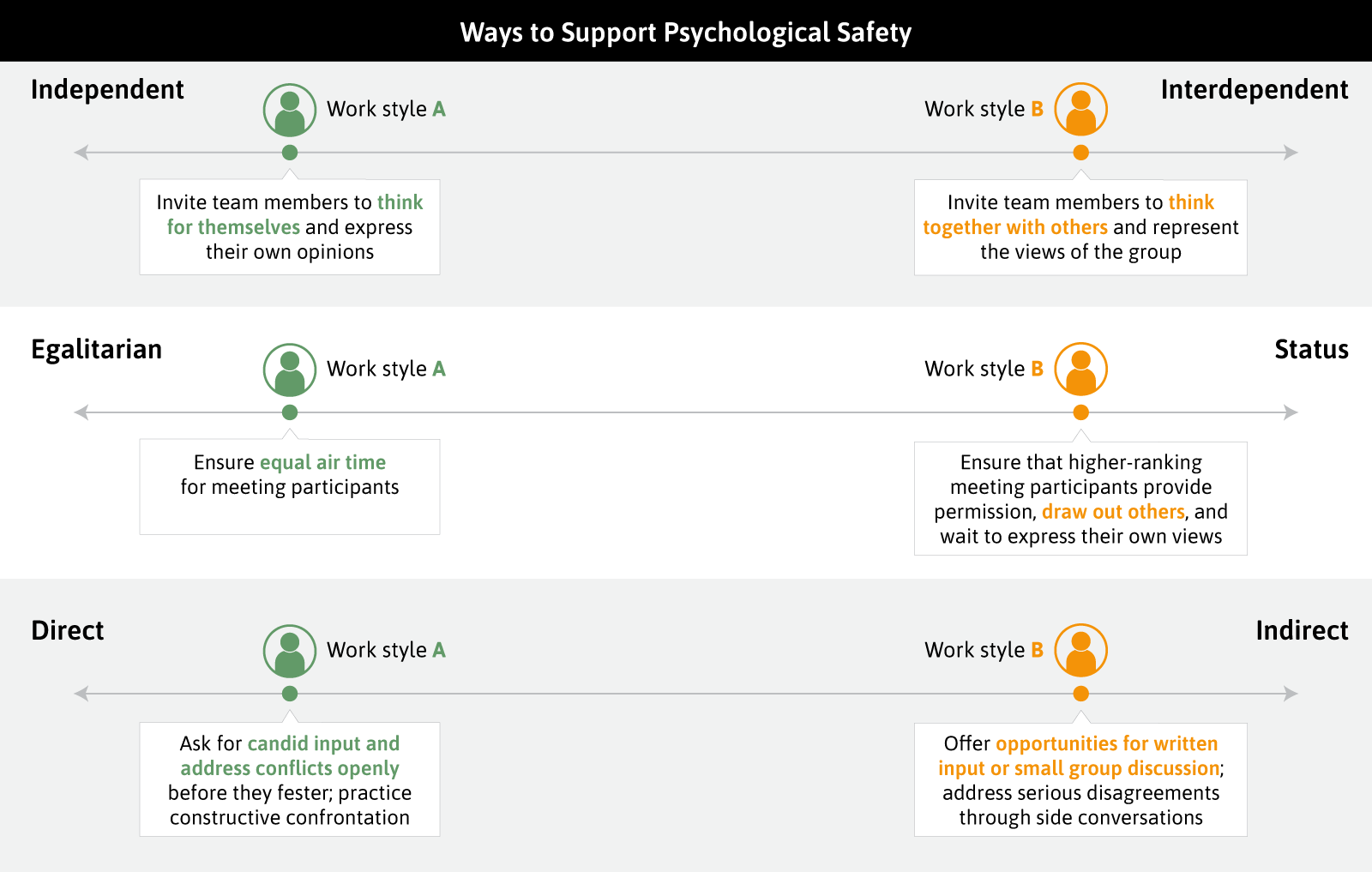

In places that tend to value more direct forms of communication, such as the U.S. and Northern Europe, common practices for reinforcing psychological safety urge individuals to express their opinions freely in a group context: “Feel free to tell us what you think!” However, this suggestion to speak up directly in more collectivist- and status-oriented societies, like China, Japan, or India, for example, may be exactly the wrong thing to do. Opinions or challenges to the status quo that cause others to “lose face” in front of colleagues can produce severe backlash, particularly when the offended person is more senior and/or politically connected. They may end up resenting the speaker for potentially endangering their hard-won status and standing within the organization. In this context, “speaking up” may sidetrack a person’s career by generating lasting animosity. But this does not mean that psychological safety is only available in certain cultural settings—there are a variety of ways to foster psychological safety, depending upon the environment. Consider the following comparisons based on three dimensions of culture:

Those who are leading in a global context, or even running a diverse team in their own home country, can benefit from understanding a variety of work styles. This will better prepare you to be flexible in creating psychological safety depending on the circumstances. Some team members, for instance, may respond well to a direct invitation to speak up, while others may feel freer expressing their views in a small group setting or in writing.

For those who bristle at the taboos of status-oriented, collectivist work styles (e.g., not directly confronting those who are more senior), take a moment to consider the possible advantages. In well-run organizations with a clear hierarchy, capable managers will often hold themselves responsible for the actions of their team members, taking blame for their mistakes and ensuring these errors don’t have an effect on their subordinates’ careers or employment status. Managers typically also provide directions, goals, and strategies while allowing team members to have a fair amount of freedom to execute tasks. This umbrella of protection and guidance provided by one’s manager creates a positive cycle of mutual trust, and team members are more determined to contribute their best ideas and to reach success because there is psychological safety.

There are cultural settings where psychological safety is indeed difficult or impossible to establish. Autocratic regimes, armed conflicts, active surveillance and repression of dissent, lack of basic access to food and other necessities, and threats to physical security all undermine any sense of safety, causing people to feel permanently on guard. However, in most major business destinations around the world, it is possible to establish psychological safety within one’s own team through the application of cultural knowledge and flexibility.

In addition to culture, many intersecting identities influence the extent to which an individual feels psychologically safe, and the stakes are higher for marginalized groups. Despite modest progress, women, and especially women of color, are still dramatically underrepresented in leadership. According to McKinsey and LeanIn.org’s Women in the Workplace 2022 report, “for every 100 men who are promoted from entry level to manager, only 87 women are promoted, and only 82 women of color are promoted. As a result, men significantly outnumber women at the manager level, and women can never catch up.” Although these statistics are from the U.S., in Asia-Pacific, by comparison, women—especially those from locally marginalized groups—are even less likely to be promoted into management roles. This enduring inequality has dramatic effects for the entire global workforce. It’s important to consider and address the burdens women are carrying with them at work, as well as what it means for your workforce when women are underrepresented in leadership.

Chances are you already work with people from different cultural backgrounds and with many intersecting identities, so it is important to ensure there are multiple accessible channels for ‘speaking up’ so everyone has the chance to do so. Consider the following:

While it may take more time and effort to embrace work-style differences and cultural nuances within your workplace, it will benefit your whole staff to respect the preferences of each individual. A deeper, more culturally informed approach to psychological safety cultivates a belief within your team that people will not be punished for who they are and the way they prefer to work, while encouraging everyone to offer their very best.