The first challenge faced by most international assignees is how to fit into their new environment. But they must soon shift from a focus on how they themselves can be included to understanding what the inclusion issues are for local employees, customers, suppliers, and community members. The most effective expatriates learn how to make a meaningful contribution to inclusion in local terms.

New assignees often struggle to balance their own personal style and previous success patterns with unfamiliar local business practices and customs. To become effective global leaders, expatriates must learn when to adapt and when to add value based on their previous experience. An expatriate’s personal concerns about inclusion in their new work environment may be further compounded at home by family members who are struggling with their own issues: learning a new language, making friends, fitting in at school, or navigating local markets and institutions to establish a household. Assignees who fail to adapt are likely to become isolated and excluded themselves.

In seeking to adapt, the first step assignees should take is to consider the similarities and differences between their own default work style and local cultural norms. For example, an expatriate with an extremely direct communication style may need to learn how to interpret messages conveyed indirectly according to local norms. Less direct messages that are communicated through facial expressions, gestures, questions, or understated observations can be rich with meaning. Similarly, an assignee who is extremely task-oriented could find that with important customers they need to take time for relationship-building before jumping into tasks in order to establish a baseline level of trust. The customer may be thinking, “How reliable and committed to our market is this new person? Are they going to take the time to learn about our business and provide follow-up service when we need it?”

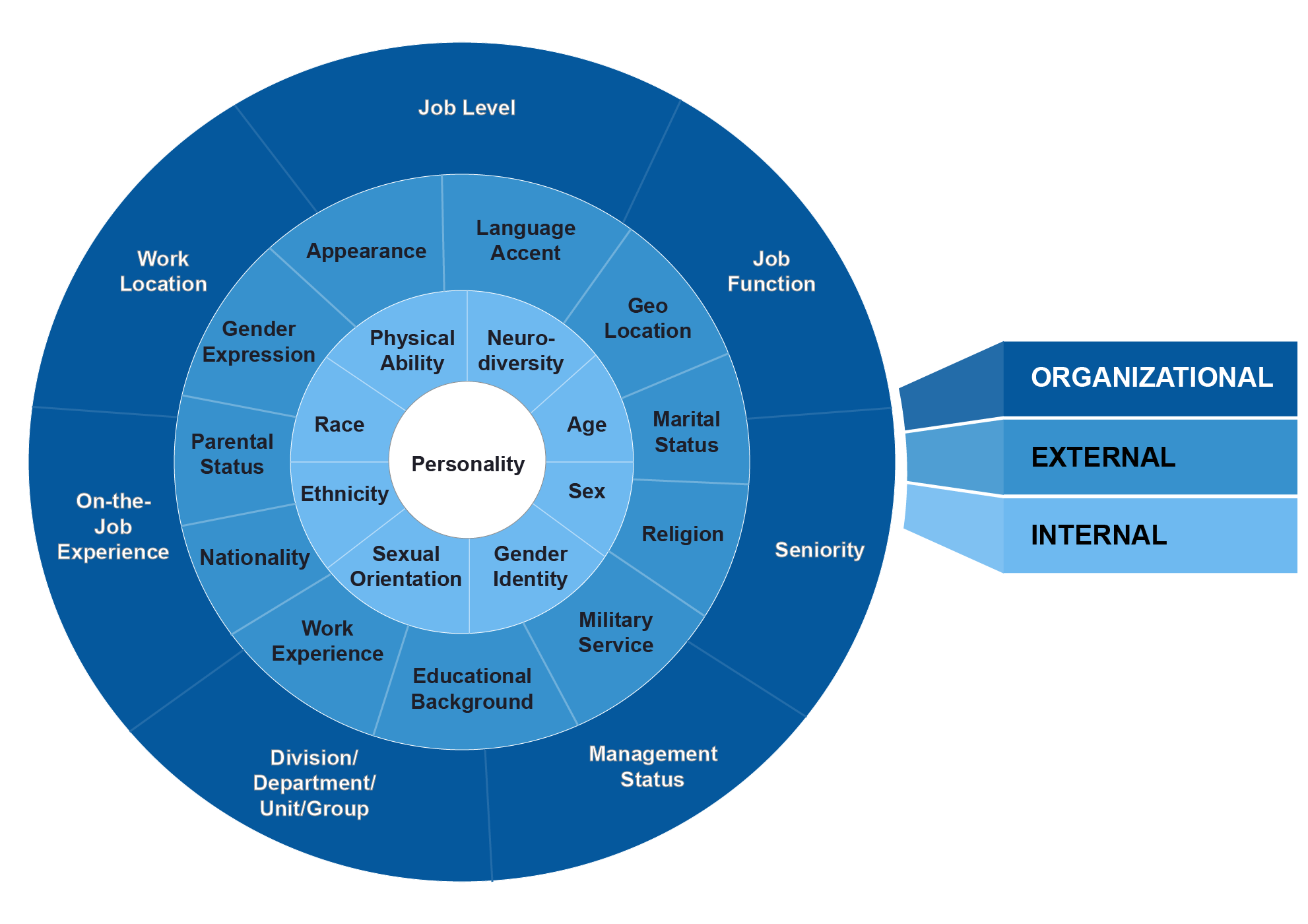

Expatriates can start by learning about general cultural contrasts; however, it is equally crucial to consider local diversity factors and ways in which people may be included or marginalized. (Click through different countries in our Global DEI Map to discover some of them.) The relevant diversity factors may include some from the following chart, and are likely to differ from the forms of diversity most prominent in assignees’ home environments.

The intersections of various types of diversity take different forms around the world. Discerning expatriates will begin to notice some connections between these factors—for instance, ethnicity, regional background, and religion—and how they influence everyday workplace patterns:

Every culture has its own forms of bias, and humans all too quickly create in-groups and out-groups. International assignees are typically under pressure from headquarters to get up to speed quickly and complete key tasks, meet objectives, or roll out new initiatives. At the same time, assignees often face choices, whether they like it or not, that will either reinforce or counteract local status quo forms of marginalization and exclusion. These could be relatively obvious, such as not hiring people from a particular ethnic or religious group, or more subtle, such as prioritizing English language skills as a promotion criterion without recognizing that these skills might reflect a particular class or caste background.

Some expatriates identify an aspect of their host culture that they find objectionable and undertake a massive change effort in direct contradiction to local customs. These large-scale efforts are difficult to implement, and could lead to unwanted attention and even retribution from government authorities who feel threatened by the proposed changes. Nonetheless, there are nearly always potential areas for change that lead to greater inclusivity—for example, increased promotion opportunities for women—that have a greater chance of gathering more widespread support. Assignees who tap into such efforts have the opportunity to make their organization an employer of choice and a champion of welcome reforms. Local employees and administrators may also grant some expatriates the latitude to implement changes precisely because they are foreigners and are seen as occupying a prestigious role.

Here are examples of changes expatriates have supported over time that have broadened inclusion with enthusiastic local employee support—of course leading-edge inclusion issues vary country by country, and even from one region to another within countries.

Expatriates must learn to adapt to a different set of cultural norms, but they are often positioned to serve as local inclusion champions as well. Rather than unwittingly reinforcing local biases, forms of marginalization, or one-sided power structures, assignees can become champions of social justice in a way that engages the aspirations of employees and benefits the whole organization. Insight into the host culture’s key diversity factors enables them to learn how and when to broaden their company’s “in-group” through more inclusive workplace practices.

—

Learn more about how Aperian can enable expatriate success through the whole assignment life cycle.