- Groups identified in Canada as “visible minorities,” ordered by their size, include South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Latin American, Arab, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean, and Japanese people.

Canada’s History

- Key features of Canada’s history help explain how it continues to differ from other parts of North America. Its first European settlers were from France, which was the dominant colonial power for more than 150 years in the land it called “New France.”

- Ethnic descendants of colonists from France who still speak French as their native language account for more than 20% of Canada’s population.

- The Revolutionary War in the 13 Anglo-American colonies to the south, which ended in 1783, had the important outcome for Canada of bringing in more than 40,000 Loyalists to the British Crown who had been expelled from or chose to leave their former homes. These new settlers, mostly of British heritage, moved under British protection to parts of Canada such as Nova Scotia and Quebec.

- The Anglo-American colonies to the south attempted to sever Canadians from British control, starting during the Revolutionary War and again during the War of 1812. For various reasons—staunch British resistance, persistent Loyalist sympathies among many Canadians, overextended supply lines, and support of many Indigenous groups for the British cause—campaigns aimed to annex Canada ultimately failed.

Canada’s Ties to Great Britain

- These early pattern-setting events placed Canada on a path to become a long-term member state within the British Empire and later one of the 54 “free and equal” Commonwealth nations around the world.

- The country moved gradually from being granted the status of a Dominion in 1867, with its own government but still under British rule, to finally gaining full independence in 1982, two centuries after the United States.

- Canada’s growing population, westward expansion, economic development, and participation in two World Wars were all shaped by continuous ties with Great Britain. Its parliamentary government mirrors British practices, as do other social institutions such as its national health care and public education systems.

Immigration to Canada

- Today almost a quarter of all Canadians have immigrated to the country. The percentage of immigrants in Canada (23%) is significantly higher than in the U.S. (15.5%) or the U.K. (12.9%), nations in which immigration has become an increasingly divisive political issue.

- There is a greater level of social consensus among Canadians regarding the value of immigration in part because their country (which borders only the U.S. and also Greenland in the far northeast) does not have a major problem with people attempting to enter illegally; the total number of illegal immigrants is currently estimated at just 150,000.

- Most immigration to Canada occurs legally and has been modified over the years to stimulate the country’s economy; it is governed by a “points” system that prioritizes job skills, education, and language proficiency.

- Sources of immigration to Canada have been shaped in part by its Commonwealth membership and refugee policies. Important countries of origin include the U.K., India, Pakistan, and Nigeria (all Commonwealth nations), as well as other countries such as China, the Philippines, Syria, and Somalia.

- South Asians from countries like India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh entered Canada in much larger numbers after immigration quotas limiting specific ethnic groups were ended in 1967, and they now constitute the nation’s largest segment of immigrants.

- More than half the population of Toronto—Canada’s largest city with almost 5 million residents—is foreign born; the BBC has called Toronto, with an estimated 250 ethnicities and 170 languages, “the most multicultural city in the world.”

Three Indigenous Groups in Canada

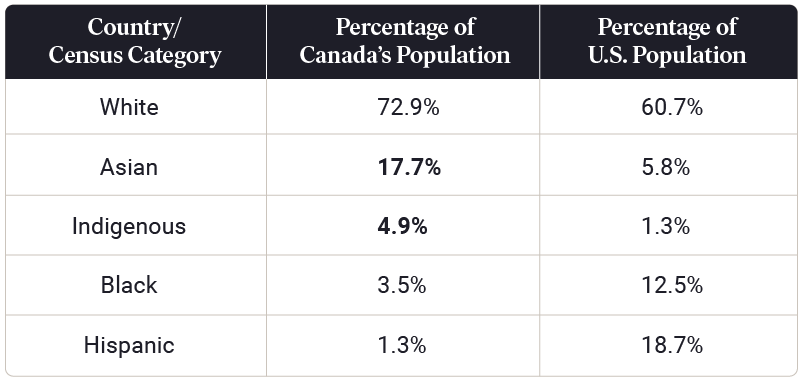

- The proportion of indigenous Canadian citizens relative to the rest of the population is more than three times higher than the proportion of Native Americans in the United States.

- Canada’s Constitution Act of 1982 officially recognizes three Indigenous categories, each regarded as distinct from the others: “These are three distinct peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.”

- First Nations (for example, the Algonquin, Coast Salish, Cree, Dakota, Mi’kmaq, Oneida, or Seneca) comprise the largest category.

- The Inuit in the far north are centered in Canada’s largest and newest territory of Nunavut.

- The Métis, a French term meaning “mixed-blood” and related to the Spanish word, “mestizo,” are primarily located in the western provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) and in northwest Ontario.

- The Indigenous population is growing at four times the rate of the national population, with a lower average age (32 vs. 41 years for non-Indigenous), and is expected to contribute to as much as one-fifth of the growth of Canada’s workforce.

Black Canadians

- After two centuries of slavery for many Black people as well as Indigenous residents of Canada—albeit on a much smaller scale than on the plantations of the U.S. south—this practice was abolished throughout most of the British Empire in the early 1800s. Canada became a major terminus of the Underground Railroad, which guided formerly enslaved people north to freedom prior to the U.S. Civil War and its Emancipation Proclamation.

- The total number of Black citizens of Canada remained small until the 1960s (about 32,000 in 1961 vs. 19 million in the U.S.). In spite of its liberal immigration policies toward new entrants from other parts of the former British Empire, until the 1960s and the Empire’s dissolution in the post-World War II era, Canada restricted the immigration of Black people from Britain’s Caribbean and African colonies.

- Once the restrictions were lifted, the number of immigrants from those areas increased sharply, although Black residents are still a relatively low percentage of Canada’s overall population—less than a quarter of the U.S. percentage. Many contemporary Black people in Canada are strongly aware of their own unique heritage and family connections with countries such as Jamaica, Haiti, or Trinidad and Tobago. Some resist the label African Canadian, similar to the hyphenated expression African-American, because they identify more readily with their Caribbean heritage and prefer the term, “Black Canadian.”

Canadian Business

- The country’s economy, the world’s 9th largest, has historically been driven by a rich supply of natural resources: petroleum, timber, vital minerals, and water for hydroelectric power and agriculture. Enormous reserves of oil and natural gas make Canada a key global player in the energy sector.

- Canadians have also achieved considerable economic diversification with the development of science and technology (there have been 14 Canadian Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, physics, and medicine), automotive and aeronautic industry manufacturing, aluminum and steel production, and a large service sector. The city of Toronto has become a major tech center, with a deep pool of skilled talent, a thriving startup ecosystem, and a hub of artificial intelligence development.

- Citizens of the U.S. next door may be surprised to learn that companies with familiar-sounding names like Shopify, Thomson Reuters, Lululemon, Suncor Energy, Constellation Software, Scotiabank, and Manulife Financial are all headquartered in Canada.

- The country’s political and commercial leadership is concentrated primarily in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Commentators have used the term “Western alienation” to describe the fact that citizens in provinces further west such as Alberta and Saskatchewan, with their more energy-dependent economies, are often more politically conservative.

- Canada’s multicultural and multilingual history, with its large numbers of Indigenous residents, the mix of French and English colonists, and subsequent waves of immigrants from many different parts of the world, is visible in most contemporary workplaces. Companies need to take into account the affirmative action requirements of Canada’s Employment Equity Act, designed to increase representation of individuals from four designated groups: women, those with disabilities, Indigenous people, and visible minorities.

Canadians can point to many accomplishments, including strong public education and a high literacy rate, substantial per capita income, a relatively small gap between rich and poor citizens, and a low level of political corruption. These achievements have been acknowledged by international measures such as the Human Development Index (which measures life expectancy, education, and per capita income), the Gini index of income inequality, and the Corruption Perceptions Index—in each case Canada scores better than its boisterous neighbor to the south. Whatever your commercial ties with Canadians or your political views might be, it is critical to understand their history and culture, which are too easily underestimated or taken for granted.

—

To see more information on Canada as well as 100+ other countries—core values, business practices, common forms of communication and leadership—log into Aperian to browse our GlobeSmart Guides cultural database. Those without access to Aperian can start a free trial that will enable them to compare their own personal work style profile with that of other countries, including Canada, along with the profiles of individual counterparts or team members.

For more information about this country and its people, download our Featured Insight on Canada.