Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives in corporate settings have become increasingly controversial. After a large spurt of growth in enthusiasm and investments in DEI initiatives over the previous several years, such efforts now face sharper questioning and criticism regarding their practical efficacy and political leanings, becoming yet another target in the U.S. “culture wars.”

DEI programs have been prohibited at some U.S. state universities, and lawsuits have already been filed seeking to expand the Supreme Court’s recent ruling against university affirmative action policies into the corporate world. These lawsuits against companies such as Comcast and Starbucks focus on policies that favor customers, contractors, or job candidates from underrepresented groups; the plaintiffs argue that quotas or preferences favoring members of any group should be prohibited.

Some organizations are now cutting back on their DEI budgets or proceeding with modified terminology, turning to related topics that are less contentious such as “wellness” or “culture.” Many have undertaken a general audit of their current practices for possible legal risks. Global DEI initiatives also have been criticized for exporting ideas and methods from their home country context to other world markets where they do not fit as well with local history and social issues, so companies are making additional changes to adapt their efforts.

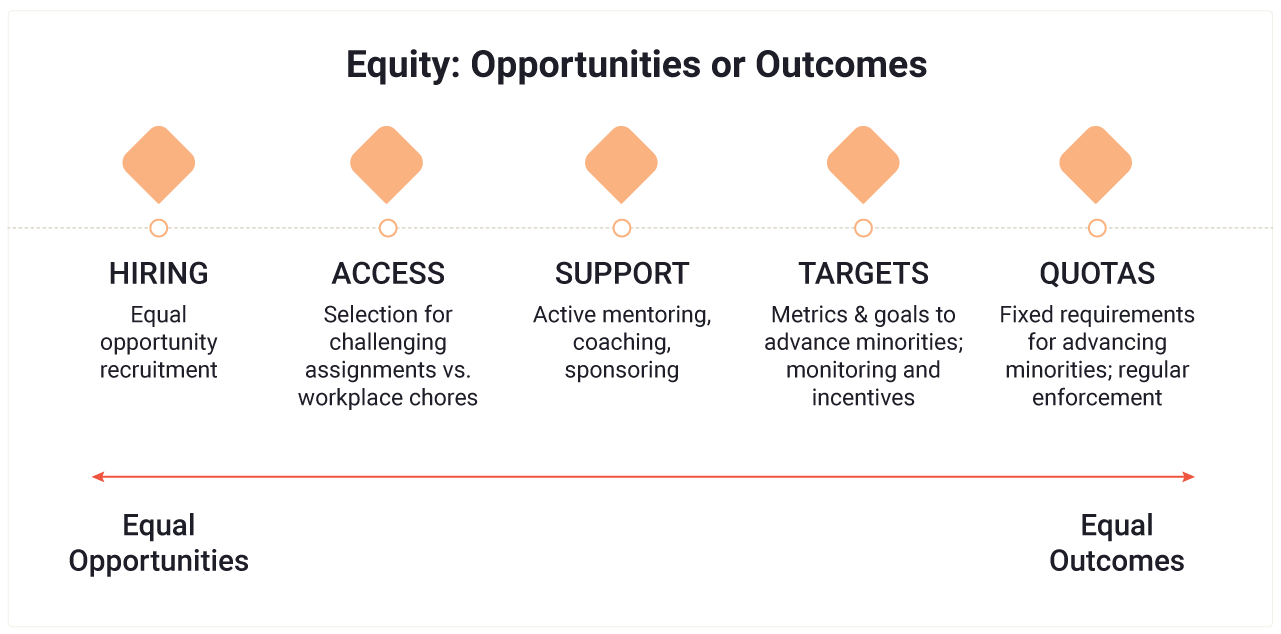

Under these trying circumstances, there have been departures of high-profile DEI leaders from various companies and a noticeable shift in the public pronouncements of corporate executives. Yet there remains an underlying commitment in many organizations to hire, develop, and promote capable employees who are members of underrepresented groups. Leadership teams can and should consider their definition of “equity” with respect to factors such as race or gender:

With DEI under scrutiny and such discussions continuing in nearly every organization, however, leaders still cannot give up on workplace inclusion, which is closely linked with employee engagement and is in fact the core value proposition of democratic societies everywhere. Most executives know that employees from any background who are fully engaged in the workplace are more likely to stay and to go the extra mile to get things done. The “who,” “what,” and “how” of inclusion require ongoing policy discussions and decisions, but inclusion itself continues to be a key ingredient of a vital workplace.

Inclusion is a perpetual human challenge, a feature of the in-group/out-group dynamic that has been part of human societies from the beginning of recorded history. Part of our basic survival makeup has been to immediately identify others as “friend” or “foe” based on their perceived degree of similarity to us. Over time, with changes in technology and forms of social organization, human groups have sought to extend their reach beyond family, clan, tribe, village, region, state, or country in order to create a more prosperous, just, and peaceful world. In the worst cases, exclusion is linked with armed conflicts and even genocide, especially when accompanied by stereotypes that demonize others and rob them of their full humanity. Unless we wish to give up on larger human societies and devolve into smaller warring factions, we need to figure out how to expand the “in-group” beyond our immediate circle.

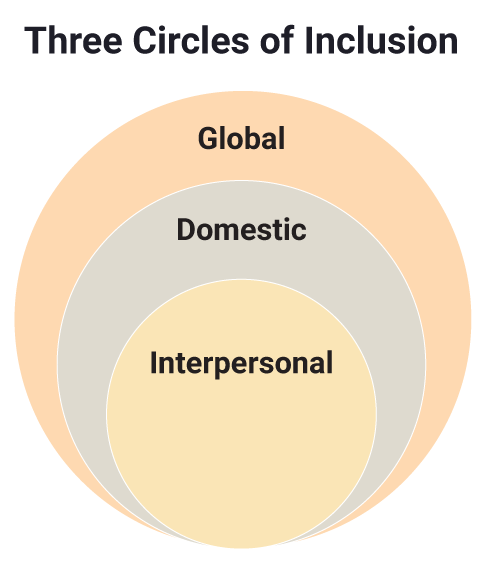

Rather than seeing “Inclusion” as merely the “I” in DEI, or as a loaded code word for various “isms,” it is more useful to view it as a series of concentric circles that affect every part of our lives, from our work with people from other cultural backgrounds, to local diversity issues, to our interpersonal relationships. The constituents of each circle are different, but the challenges and necessary inclusion skills overlap. There are sensible, practical, kind, and courageous actions we can take at each level to create a more inclusive environment, embracing not just those who are like us, but those who are different.

It is often easiest to perceive differences between ourselves and people from other cultures. Such cross-cultural contacts have become increasingly frequent, even with rising geopolitical tensions. Organizations need to be able to attract and retain the best global talent, ensure smooth and effective collaboration across national and cultural boundaries, and ultimately enable employees to rise to higher-level roles based on their performance rather than their personal background or location. Anyone who is traveling or living abroad on business, part of a global team, dealing virtually with an offshore shared services employee, or working with colleagues down the hallway who are originally from other countries is likely to get far better results through intentional acts of inclusion. Here are a few sample inclusive practices that nearly every organization can benefit from:

On a more local level, it is important to consider what groups or individuals have been marginalized in your environment based on some aspect of their background: race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, ability, regional or educational background, socioeconomic status, language, and so on. There are relatively straightforward actions that organizations and employees can safely take to address these marginalization issues:

It is natural to enjoy the comfort of being around like-minded people with similar backgrounds. Reaching out to others who are different in some way requires greater effort. Yet if we only associate with those who are like us, our world may become increasingly narrow, rigid, and fearful. How broad are our social circles? How can we gain access to new information? What kind of person do we aspire to be? Successful societies and their economies balance individual interests with altruism, and the most successful leaders tend to be surprisingly humble and willing to give credit to others (see Jim Collins on Level 5 Leadership). In our own daily lives we can become more inclusive of differences in a way that primes us to be champions of global and domestic workplace inclusion as well:

Inclusion continues to be an ever-present challenge, and organizations that are not inclusive of people from different backgrounds will likely find that this affects their business outcomes in a negative way. No employee wants to feel excluded or treated as a second-class citizen. Inclusion is connected to basic human desires to be a full-fledged group member and to have fair workplace opportunities to grow and prosper like anyone else. Difficult and contentious though inclusion sometimes may be, a world without it would be one with little promise or hope.

We can’t include everyone all the time—there are always limits to our physical and mental resources, clashing views about how much inclusion is enough, and legitimate questions about how we can work together most efficiently. On the other hand, as the number of people on our planet increases toward nine billion, with most of this population growth occurring in emerging markets, we all have to stretch ourselves to live together in ways that are peaceful and mutually beneficial. What John F. Kennedy said more than sixty years ago about the then wildly ambitious goal of traveling to the moon could also be said about inclusion today. “Why choose this as our goal?” We do these things “not because they are easy, but because they are hard…because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

—

Start a free trial of Aperian to grow cultural awareness and inclusion within your global teams.