Neurodiversity is a broad term covering a variety of conditions, each of which has a range of manifestations from mild to more acute. There are numerous diagnostic labels, sometimes with overlapping symptoms. Among those most frequently cited are Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Extreme Social Withdrawal (ESD), Bipolar Disorder, dyslexia, dyspraxia, synesthesia, Tourette Syndrome, schizophrenia, and psychosis.

Most larger companies and many smaller ones already have employees, including top executives, who are neurodivergent. However, these employees frequently choose not to share their condition with others for fear of negative stereotyping and ostracism. Organizations willing to be more inclusive of people who are neurodivergent are likely to find they have access to a wider pool of talented individuals that are able and willing to contribute, while enhancing the engagement of all employees.

Common terms related to neurodiversity include:

Autism Spectrum Disorder, for example, affects an estimated 60 million people worldwide and is the topic of much current social discussion and research. ASD is commonly linked to difficulties with social interactions, including limited communication of thoughts or feelings, extremes of hypersensitivity or non-responsiveness, and often a narrow range of interests. These can be accompanied by physical symptoms such as lack of eye contact, discomfort with touch, sensitivity to light or noise, or repetitive self-soothing movements like spinning or rocking.

Researchers estimate that 90% of working-age adults with ASD are either not working or underemployed. Yet ASD is also linked with capabilities for intense concentration, pattern recognition, attention to detail, and breakthrough discoveries with major scientific, commercial, or social implications. Among the famous public figures who have manifested common symptoms of autism and acknowledged their condition are serial entrepreneurs Sir Richard Branson and Elon Musk, the youthful climate change activist Greta Thunberg, Dr. Temple Grandin, who revolutionized the treatment of livestock, Satoshi Tajiri, creator of Pokémon, and the comedian Dan Aykroyd (Saturday Night Live, Ghostbusters).

Pioneering advocates for the distinctive strengths of some people with autism have created a new appreciation for their potential in the workplace and beyond. Dr. Temple Grandin was also an early and outspoken advocate for the capabilities of autistic individuals. Employers or potential employers seeking to build a workplace environment that embraces neurodiversity must be able to support people who are unlike their colleagues while drawing out their unique talents.

Different global social contexts shape organizational approaches to neurodiversity. Within many countries, approaches may also vary depending on factors such as family resources, regional setting, or industry; it is important to understand the particular combination of factors in each location.

In Pakistan, for instance, the predominant response to conditions such as ASD has long been avoidance. There is both a negative social stigma attached to what are seen as mental disabilities, and a lack of medical professionals with the background and training to offer support. Fazli Azeem, a Pakistani advocate for people with ASD, describes his experience:

When I approached local doctors and pediatricians and psychologists in the leading private hospital in my city, all of them refused, stating that in their experience, no one in Pakistan was qualified to do adult diagnosis for anyone on the Autism spectrum. Over the years, I have been contacted, called and emailed and have even met a few adults on the Autism spectrum in Pakistan. Their families told me that they were diagnosed while they were outside Pakistan and even after diagnosis, they did not want even other family members to know about it, due to the social stigma of disability or being different.

Circumstances in Pakistan and elsewhere in the region have recently begun to change, with autism care centers opening up in major cities such as Karachi and Rawalpindi, and non-profit groups like the Autism Society of Pakistan providing support for children and their families while promoting greater public awareness and medical research.

For decades, critics and social scientists in Japan have described the phenomenon known as hikikomori (translated literally as “pulling inward,” “being confined”), a form of extreme social withdrawal. Researchers note a significant overlap between people who are hikikomori and those with an ASD diagnosis. In a collectivist society such as Japan, factors such as bullying, shame about being different from other group members, and the fear of offending others and being rejected by them all contribute to social anxiety and withdrawal.

Although this hikikomori condition was first noted when children refused to go to school, it has now been linked to a generation of Japanese who are between forty and sixty years of age. Many members of Japan’s so-called “Lost Generation” were unable to find full-time employment during the country’s prolonged economic downturn, with a variety of severe social consequences. Another term used in Japan, the “8050” problem, refers to people in their 50s who are socially isolated and living with parents who are in their 80s. Three and a half million Japanese in their 40s and 50s have not married and are still living with their parents, including more than 600,000 who are classified as middle-aged hikikomori shut-ins. Most of these people are either underpaid and underutilized if they are working, or completely excluded from employment opportunities.

There are glimmers of hope for Japan’s neurodiverse people in this otherwise gloomy picture. Online gaming has addictive qualities that can cause users to withdraw from face-to-face social interactions; the structure, intensity, and limited requirements for social interaction of gaming appeal to many with an ASD diagnosis. Satoshi Tajiri, inventor of the wildly popular Pokemon Go, is himself on the autism spectrum—his game actually encourages and reinforces behaviors that expand social contacts. This game has special value for hikikomori with symptoms of autism that include Extreme Social Withdrawal (ESW).

Pokémon Go… has its participants physically traveling to new locations in the real world to “catch pokémon” and they get rewarded with unique, in-game prizes from different locations. This game encourages people with ESW, through a platform exciting to them, to go outside their comfort zones where they will be rewarded. Games like Pokémon Go are an attractive way to get people to re-engage with the world and people around them. [32]

Japan’s corporate sector is also showing early signs of a changing approach to neurodiversity. Startup subsidiaries of major companies such as JGC Engineering and the recruiting firm Persol Holdings specialize in hiring people who are neurodivergent. These employees, who are provided with a variety of accommodations such as self-paced tasks and the option for remote work, serve clients with their skills in IT, data analysis, machine learning, and AI engineering. Whether this trend toward more inclusive Japanese workplaces will gather further momentum remains to be seen.

Although the exclusion of people who are neurodivergent has also generally been the norm in Europe and the U.S. as well, like their Japanese multinational counterparts a growing number of companies have been experimenting successfully with new approaches. Managers of neurodiverse employees point to increases in productivity, innovation, product quality, and employee engagement. In addition to the potential contributions of those diagnosed with ASD, there are people with other conditions who can have a positive impact for their employers. ADHD, for example, often appears in the form of challenges with time management, following instructions, or meeting deadlines; however, it has also been linked with lateral thinking, creativity, and a readiness to take risks. Similarly, dyslexia is associated not only with language skills difficulties (in reading, writing, spelling), but also with special abilities in areas such as art, computer science, or design.

Examples of companies that have taken the lead in embracing neurodiversity include SAP and Ernst & Young (EY). Germany-based SAP, which sells enterprise software, introduced its “Autism at Work” program over a decade ago. This program has opened up job opportunities for more than 200 employees diagnosed with autism in 15 countries, now working in areas such as software development, finance, and customer support. Beyond its hiring process—which includes “do-the-work” skill assessments rather than relying primarily on interviews that neurodivergent individuals might find overly stressful—SAP has also broadened its support to incorporate “team management and greater flexibility to empower neurodivergent employees with career pathways that allow them to apply their unique skills and perspectives to tasks and opportunities.” One feature of this ongoing initiative is training for SAP employees at all levels across the company on neurodiversity to build awareness, empathy, and communication.

EY, with its enormous workforce of 400,000 employees, has taken the additional step of establishing regional and international centers of excellence for neurodiversity. These centers disseminate best practices and promote collaboration between regions. EY has also created its own externally facing business line called “neurodiversity-powered transformation” that promises to accelerate emerging technologies and apply “intelligent innovation” to clients’ digital and workforce needs through contributions from its neurodivergent workforce. The company asserts, “One talent segment capable of delivering exponential value has largely gone untapped. Utilizing the talents of neurodivergent people can help companies unlock their full potential.”

Although country environments differ and approaches to neurodiversity in many places are evolving rapidly, there are still common challenges for everyone.

One of the thorniest issues facing both neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals is the so-called “double empathy problem.” Dr. Damian Milton, who coined this term, claims that breakdowns in communication between autistic and non-autistic people are not simply a result of the social limitations of those who are autistic. He suggests that such breakdowns are due instead to the fact that autistic individuals process emotions differently, and that understanding and communication is a two-way street. It is easier for people who process messages and emotions similarly to empathize with each other, and we all struggle to understand those who are different from us. “When people with very different experiences of the world interact with one another, they will struggle to empathize with each other.” Milton notes that language differences can make mutual understanding more difficult. “Cross-neurological” gaps in understanding are likely compounded by cross-cultural contrasts, making it even harder to empathize with a neurodivergent person from a different cultural background.

As companies increasingly seek to hire neurodivergent employees, training for their managers and for other employees becomes critical, especially to address the double empathy problem. Training to build greater mutual understanding, empathy, and effective teamwork can be useful for both neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. Here are a few key guidelines from the growing set of information and best practices for managers:

Another important facet of manager training largely unexplored until recently is the intersection of neurodiversity and culture, which takes multiple forms.

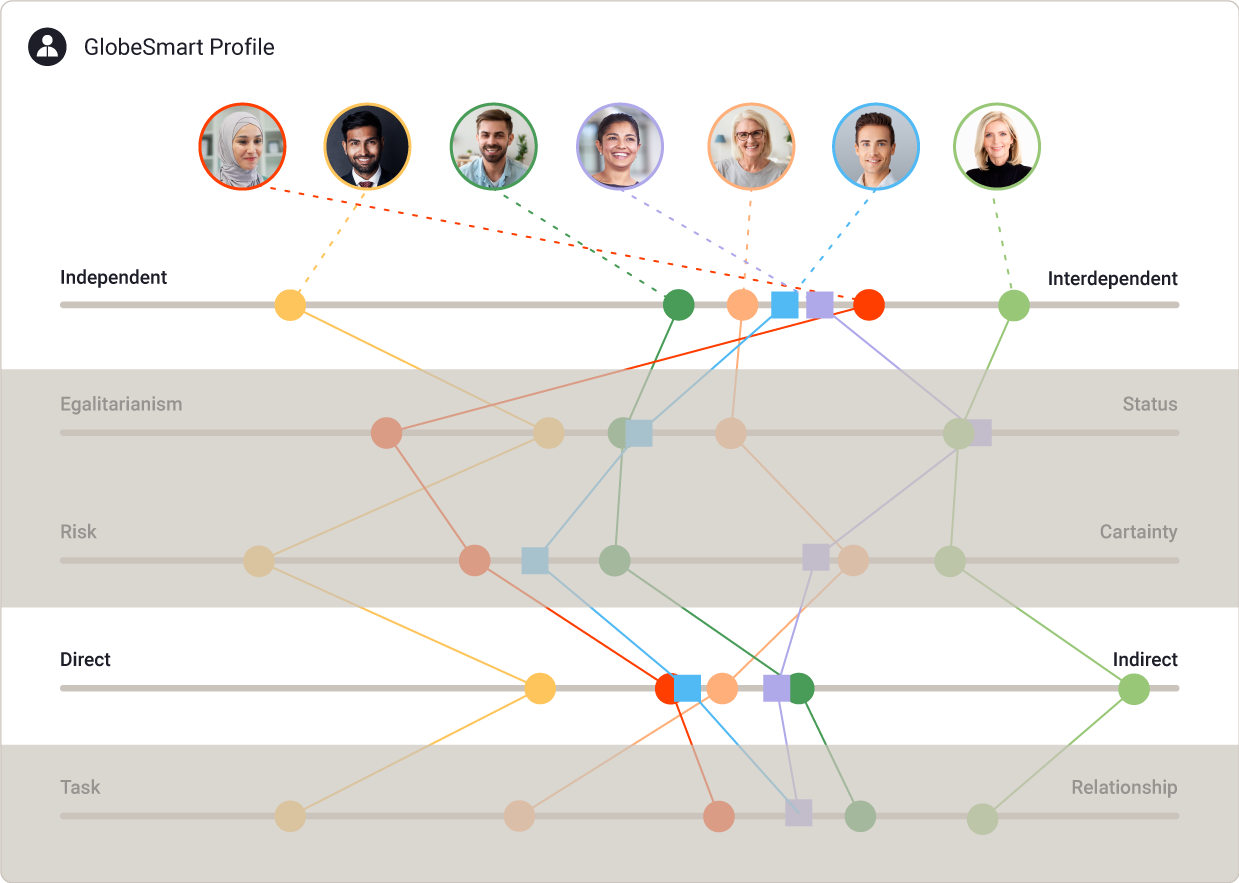

For example, avoidance of eye contact by many people with autism may be regarded in more egalitarian cultural settings as a sign that a person is unable to communicate effectively, while in more status-oriented cultures, it could be interpreted as a form of respect. Likewise, depending on the cultural context, the extreme attention to detail often present with autism or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) may be seen either as an obstacle to taking reasonable risks, or a welcome form of ensuring greater certainty. Managers of neurodiverse employees in a multicultural team setting need to be particularly aware of their personal work style and not misinterpret a team member’s behavior based on their own cultural background.

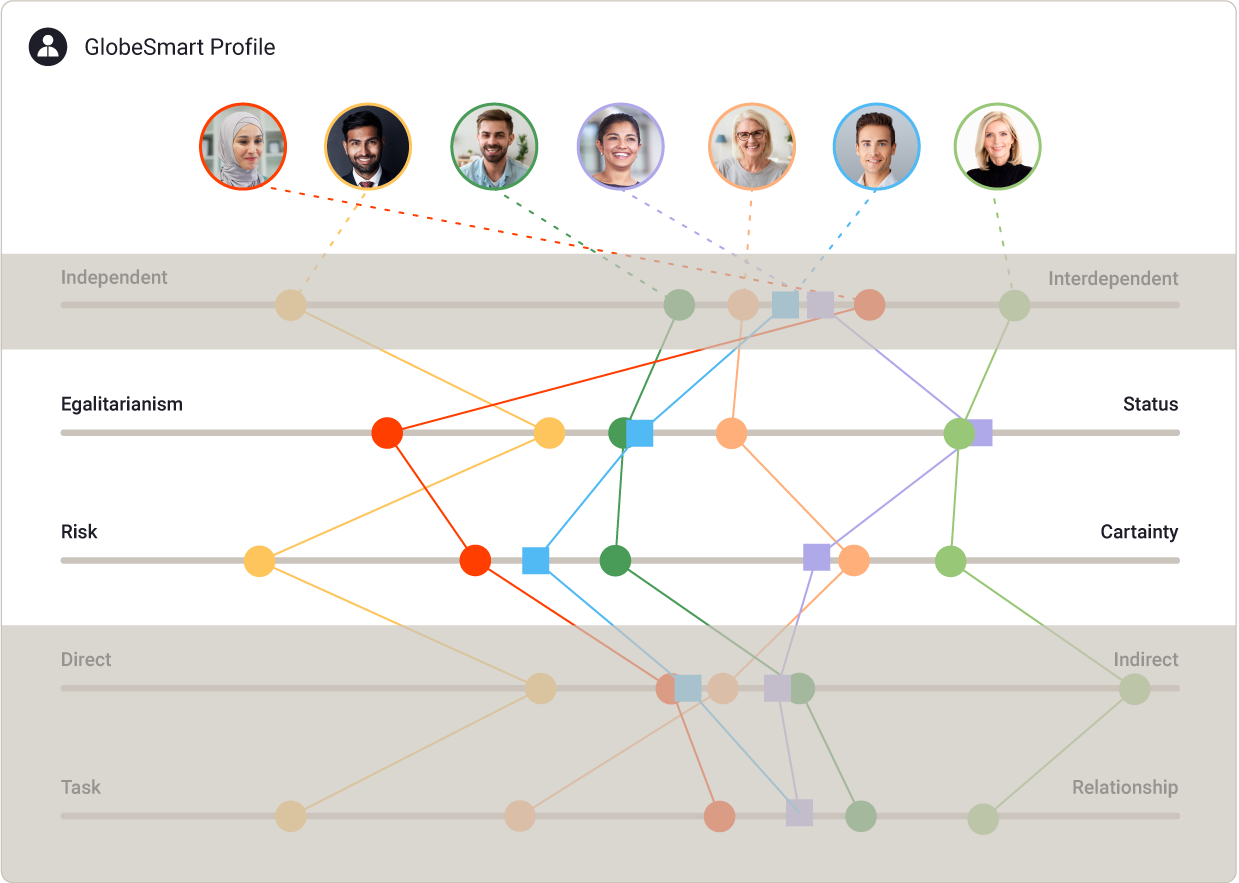

Reevaluating behaviors normally regarded as “atypical,” or beyond the normal range, can also help to build mutual empathy. Neurodivergent individuals engage in a wide variety of behaviors, including some that are at both extremes of each cultural dimension. For instance, a person with autism may either need to be completely independent and isolated for some period of time, as is common with Japan’s hikikomori. For those who are employed, this could require working from a solo location wearing noise-canceling headphones. Others, such as people with either autism or ADHD, may have the interdependent need for a “body double” to get started, stay focused on tasks, or meet deadlines. Autistic people can also be shockingly direct in their comments and seemingly insensitive to workplace social norms or business practices—a characteristic that could be desirable in environments that need to become more innovative. On the other hand, the autistic behaviors of physical withdrawal or extreme reticence may seem quite indirect and uncommunicative. In short, those who are neurodivergent also have “spiky” work style tendencies that are at times expressed with greater intensity on one side or the other of the usual continuum of behaviors.

Fortunately, the basic skill set for cross-neurological and cross-cultural teamwork is the same, although some neurodiverse conditions pose more severe workplace challenges. Both neurodivergent and neurotypical employees can benefit from greater self-awareness, other awareness, and bridge-building between different perspectives and work styles. Managers who acquire and apply this skill set will find it a continuous source of fresh insight and progress toward reaching shared goals. In the process of bridge-building, instead of labeling and distancing a counterpart for being divergent or typical, we recognize others as being another form of a more inclusive “us.”

Aperian helps teams thrive by leveraging the similarities and differences among them. Our new learning module, Creating a Neuroinclusive Workplace, helps organizations leverage neurodiversity by implementing inclusive solutions that can benefit all employees. Contact us for more information about this learning experience and how Aperian can support your workforce.