I’ll start by saying this may be a rant.

We see that well-crafted and expensive programs to fill the leadership pipeline for women are sometimes a hit and sometimes—a miss. They can be at least partly a hit because everyone has the best intentions, and there is genuine effort that goes into defining clear learning objectives, outcomes, and accountability for the women who participate in these programs. Yet decades of well-intentioned efforts have produced limited results, even in the face of increasing competition for talent across the Asia-Pacific region that keeps ratcheting up the stakes. Gender inequities in much of APAC still tend to be particularly striking and persistent in comparison with other regions.

What is missing and why should we care?

If our collective end goal is to increase female participation in the Asia-Pacific workforce, especially in leadership, why are we still seeing trends such as these?

There has been progress over the last decade or two in terms of opportunities for women to enter the workforce and rise within their organizations. I have to stop here and feel grateful and applaud all the efforts that got us to where we are today. However, we have identified a problem—that even now, after generations of struggle, women don’t get equal access to opportunity and are denied the chances they deserve.

What I find hardest to accept is that in most organizations women are yet again forced to take the primary ownership and accountability for further progress. Our attempts at solutions seem to be recreating and amplifying one of the same problems that is a barrier for women—namely, expecting women to do even more.

Yes, some women have self-limiting beliefs and may experience “imposter syndrome” when taking on new roles after centuries of hearing a different narrative. However, focusing on such mindset obstacles alone can cause women who may not face these hurdles to reconsider the abilities of their female peers and reinforce negative messages for those who are already struggling. This vicious cycle has been aptly described by the 2021 HBR article, “Stop Telling Women They Have Imposter Syndrome,” by Ruchika Tulshyan and Jodi-Ann Burey.

Should we stop making women themselves accountable for change? No, this is not what I am suggesting. Women are vital change agents as they experience inequities first-hand and bring with them passion and grit that is much needed to create change. We have made a good start and need to continue this for sure. But this is one piece of the puzzle and, I would argue, perhaps not the most significant one. What we need equally if not more so is to build systems and platforms to engage and support women in a more holistic way. The onus is on everyone to drive systemic change and build workplaces that are welcoming for women so they can step in and thrive.

As we begin to look for more systemic solutions, it is necessary to identify and solve for the overlapping set of barriers that hold women back despite them having the right attitudes and skills.

Focusing for the moment on workplace issues and the talent cycle, one area stands out: the promotion process. Countless companies face some variation of the same problem: they hire large numbers of capable women, but along the career path too many of these women are left behind. Those promoted into management and ultimately into executive leadership roles are far fewer than the number of men.

Maternity leave or greater household responsibilities may be partial reasons for this, and organizations can find ways to support women such as flex-time, daycare support, ongoing career path development, and so on. But there is another, deeper issue: most women are being assessed by managers (male or female) according to their own subjective standards, with nearly all top leadership role models being male—sometimes non-Asian.

Women who attempt to advance in their organizations according to standards defined by a different gender or culture may be judged as failing to achieve just the right degree of assertiveness, decisiveness, or risk-taking. This classic “no-win” situation, often described as a “tightrope,” makes it somewhat surprising that any women at all are able to attain top leadership positions. It has been partially countered by training and coaching more women to become aware of the required balancing act, while learning how to navigate carefully. But is there something else that can be done? Something that women alone don’t need to own by themselves? How can we create a broad avenue for women’s advancement rather than a precarious tightrope?

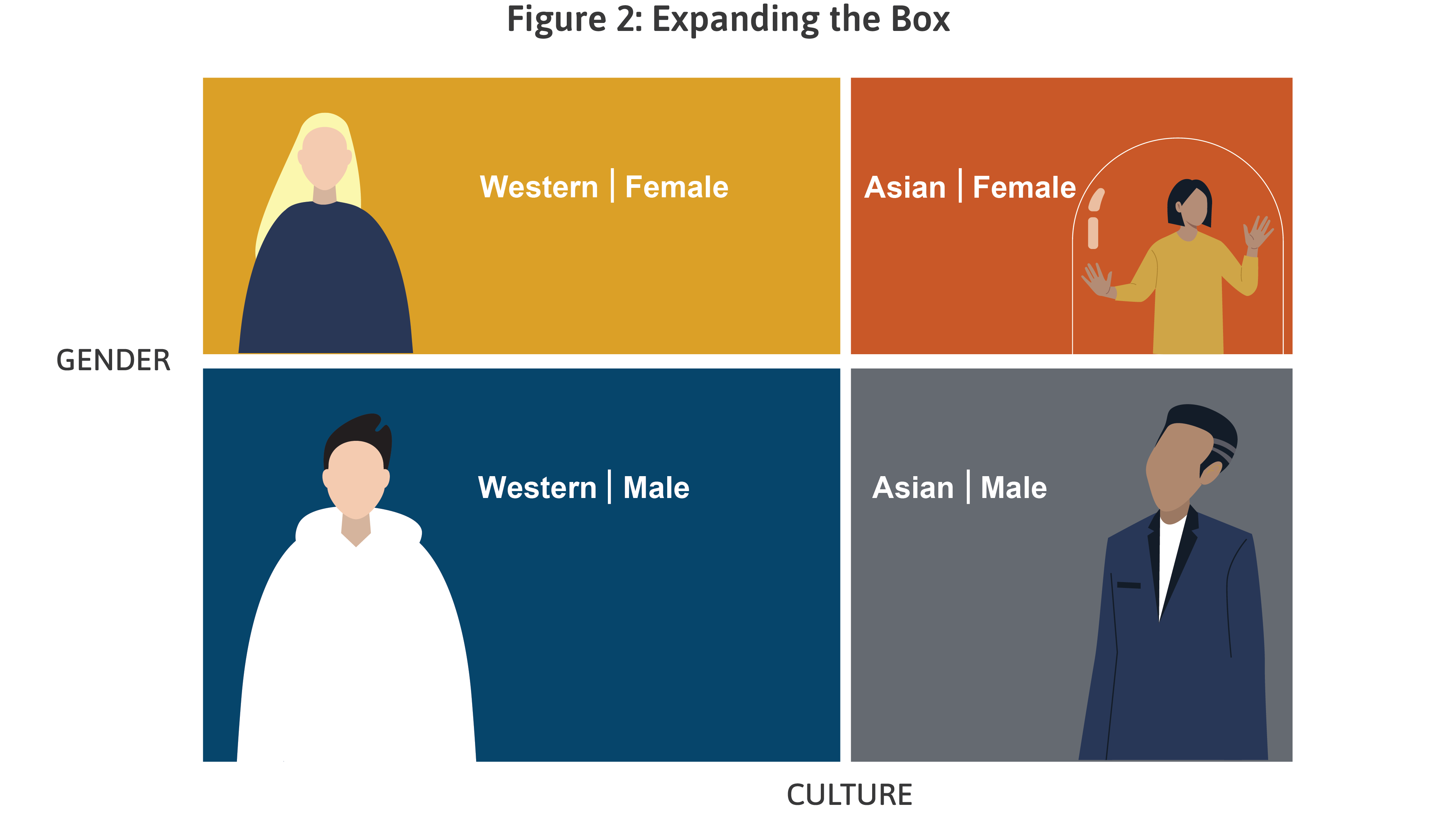

Note: This graphic could be further expanded to consider the intersectional identities of LGBT+ women or women from marginalized communities who are even more neglected when it comes to defining and assessing leadership capability.

The four-box matrix displayed above, created by Aperian’s Director of APAC Consulting, Mui Hwa Ng, helps us consider the yardstick by which we are assessing women’s capabilities for leadership. Competencies or styles that are imported from the West tend to predominate. In addition, Asia’s male executives and their leadership role models also exert considerable influence in the talent assessment process, with the result that the value and capability of Asian Women is being reviewed based on benchmarks created by and for others.

So if an organization has overly narrow parameters for what defines a high potential leader, how can it expand the box? First they must reexamine their leadership assessment processes to encompass a broader range of leadership capabilities and styles. There is also a need to consider what future leaders will look like, and the answer for Asian leaders is likely to require a major revision of our previous assumptions.

The question of how men and women are similar or different is a fraught topic that has been the subject of a great deal of research. Asia-Pacific data from over 10,500 users of our own GlobeSmart Profile tool points to several statistically significant differences that are correlated with respondents’ gender background. Average scores for the Asia-Pacific region across this very large sample indicate, for instance, that men tend to be relatively more risk-oriented, while women tend to be more certainty-oriented. Of course individual women or men may have their own unique scoring patterns, and there are some women who are more risk-oriented than their male counterparts, but on a broad scale men and women do tend to respond somewhat differently.

There are a variety of potential reasons that might account for different gender-based responses: genetics, childhood socialization, the functional roles (e.g., sales vs. finance) that are most common for men or women in APAC, or ways that the workplace performance of men and women is scrutinized and rewarded by others. As Catherine H. Tinsley and Robin J. Ely note, “Because women operate under a higher-resolution microscope than their male counterparts do, their mistakes and failures are scrutinized more carefully and punished more severely.”

Regardless of the best explanation for such gender differences, standard leadership competency and assessment models generally highlight and reward strategic risk-taking behaviors more than a certainty orientation aimed at risk mitigation. It becomes easy to see how a system that fails to take into account both gender and cultural differences would tend to disadvantage women in Asia-Pacific overall.

However, both risk-taking and certainty are important, as are other areas in which members of a diverse workforce contribute complementary strengths. It is essential for organizations to take calculated risks to develop new products and expand into new markets, and to provide their customers with the certainty that they will receive high-quality products on schedule and with superior service. So one way to calibrate assessment and promotion systems to support women’s development could be to acknowledge and reward both risk and certainty-oriented behaviors and to encourage the development of both.

To make real progress in women’s leadership development, the focus needs to be more on organizational systems and support factors, and less on getting women to yet again speak up, to be more, and to do more.

Best practice approaches we recommend are to:

Through our work at Aperian in APAC and beyond, we know that deeper understanding of culture and gender, along with the application of best practices like those outlined here, enables both women and men to thrive in the global workforce.

Get in touch with us today to discuss new ways to support the development of women leaders in Asia-Pacific.

Special thanks to Dr. Ernest Gundling and Mui Hwa Ng for your contributions, collaboration and thoughtful review.

Inclusive Leadership, Global Impact

Our World in Data: Women’s Employment

Our World in Data: Proportion of women participating in the labor force, 2013-2020