We often hear that diverse teams are more innovative and perform at a higher level. But just having a mix of team members with different gender, racial, or cultural identities does not guarantee positive performance outcomes. Decades of evidence indicate that cultural diversity in particular presents a double-edged sword: “More diverse teams experience the process gain of increased creativity, but also the process loss of increased task conflict.” Multicultural teams face a variety of distinctive obstacles that can impede or limit their performance. These include:

Diverse teams must be able to both “diverge,” tapping the full range of ideas and perspectives that are available to them, and also “converge” in a way that enables them to eventually integrate different perspectives, build a shared plan, and align around next steps to accomplish their goals. Academic research and practical experience over the last several decades have demonstrated that without divergence and convergence, teams can become locked in conflict between divergent views and fail to realize their creative potential. Three areas that require special attention from multicultural team members and their leaders are matrix priorities, cultural competence, and hybrid team facilitation.

Large organizations typically have some form of matrix reporting structure. “Matrix teams,” get their name from the fact that they may include members from more than one country or region, business unit, organizational function, or product group.

The challenge for matrix teams is that their members can readily be pulled in various directions by their other work. Different reporting relationships, metrics, strategic objectives, or customer demands may all draw team members apart, sometimes leading them to blame each other for sparking conflicts or behaving in untrustworthy ways.

In order to head off such issues and to set up a matrix team for success, or even to decide whether the team can be successful at all, here are six key questions to pose at the outset of the team’s work.

If the answers to any one of these questions are vague or worrisome, it is best to resolve them before embarking on a matrix team effort. Teams that are already in motion can review their interactions so far to determine whether there are underlying matrix issues that they need to address.

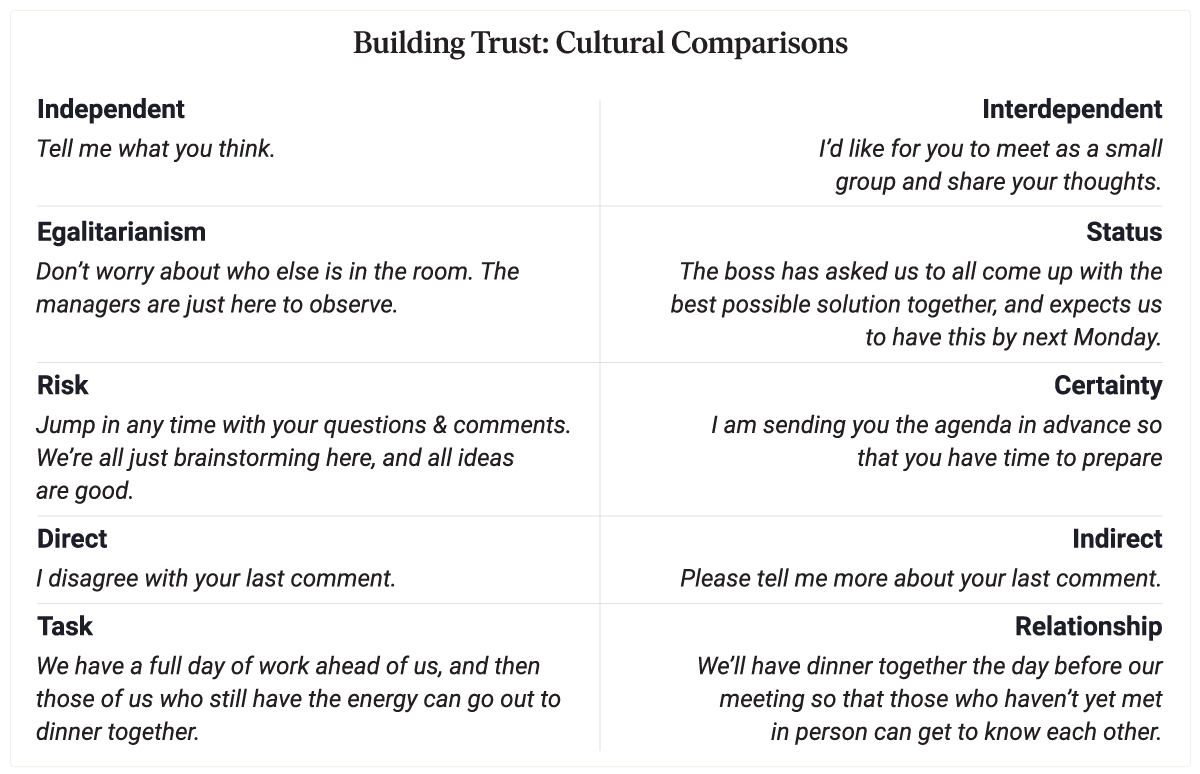

Trust is a key foundational element of effective teamwork, however, the behaviors related to building trust—along with other essential components of teamwork such as communication, delegation, problem solving, or decision making—vary considerably from culture to culture. Standard practices in a monocultural team environment frequently do not lead to the desired outcomes in a multicultural setting.

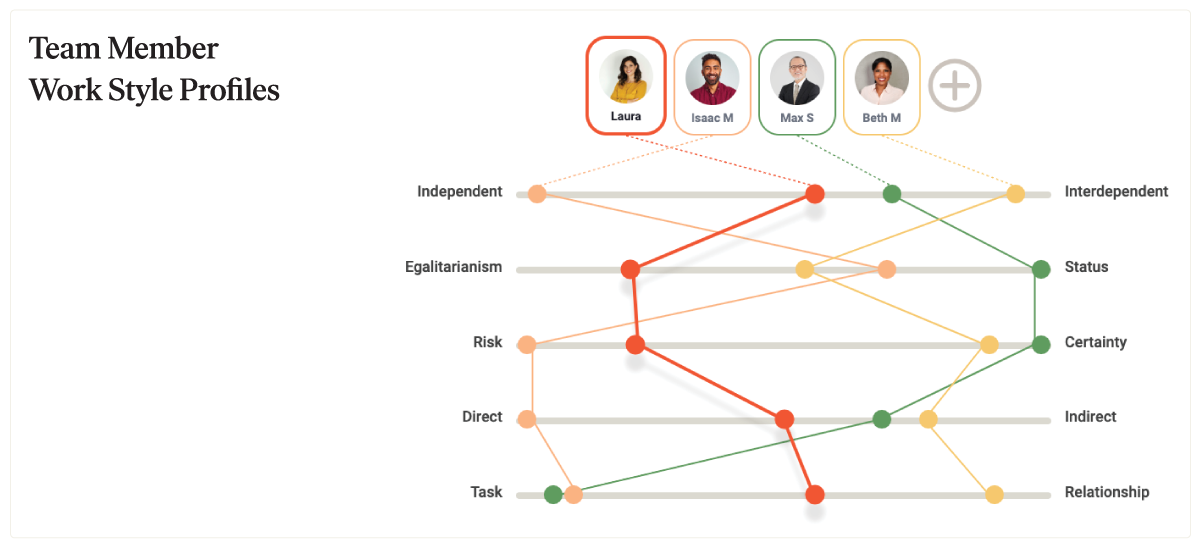

For multicultural teams, understanding the work styles and cultural backgrounds of team members is often the best way to start building trust and begin the journey toward successful divergence and convergence. Below is a sample set of Profiles for members of a global team. Note the range of individual profiles for each of the five dimensions.

The team member represented in green on the left, for instance, has a work style that is relatively independent, egalitarian, risk-oriented, direct, and task-focused. This person likely holds a very different set of assumptions about how best to build trust (“Tell me what you think!”) compared with the team members whose Profiles are toward the right side of the scale (“Let’s meet in small groups to discuss”). For a multicultural team, it is essential for team members, and especially the team leader, to have sufficient cultural competence so that they are able to take a flexible approach to building trust.

Beyond trust-building, there are other challenges that affect multicultural team performance. A team leader with a very independent work style, for example, may find it difficult to work with or supervise interdependent team members who expect to engage in joint problem-solving with frequent check-ins. This team’s decision-making process could also be affected by different attitudes toward risk; some more risk-oriented team participants may feel that the team is ready to move forward with a decision, while others who are more certainty-oriented believe it is still essential to gather additional data and finalize detailed plans.

Cultural competence enables team members to avoid the pitfall of assumed similarity—assuming that others are more similar to us than they actually are—and to begin to mediate between contrasting work styles. When team members understand why and how others behave differently, they can consider how to engage in mutual style-switching so that the team develops its own shared style, diverging and converging in ways that leverage the strengths and capabilities of each person.

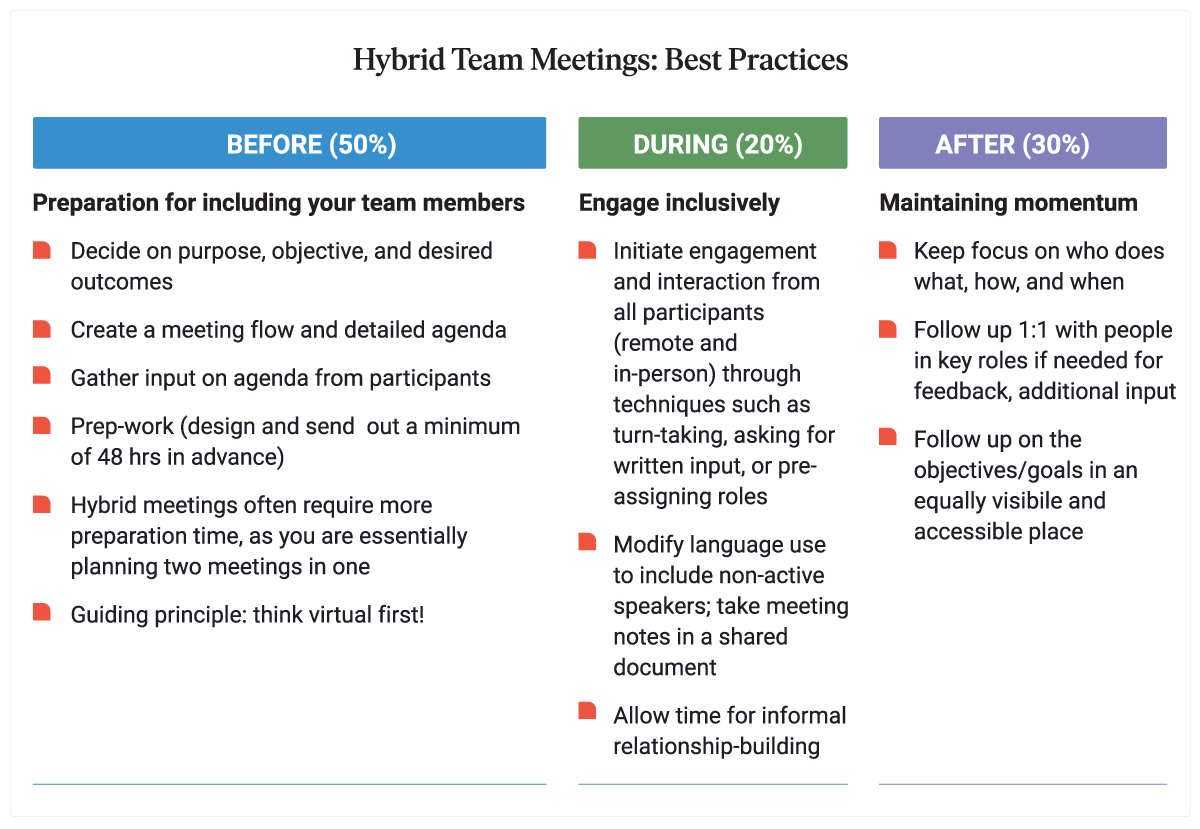

When matrix stakeholder interests are well-coordinated and team members have a baseline set of cultural skills, effective facilitation techniques can substantially accelerate the ability of team members to both diverge and converge to achieve common goals. In recent years there has been a vast expansion of the amount of work that teams are conducting virtually or in a hybrid virtual and face-to-face format. With multicultural teams in particular, it has become increasingly essential to implement and maintain best practices for hybrid teamwork.

Meetings are a key way teams interact, and the following steps for before, during, and after meetings can substantially improve them.

Additionally, for teams that deal with time zone differences, it can help to “share the pain”—that is, to vary meeting times so that the same people are not always asked to join meetings late at night or early in the morning. This helps to ensure that each team member has the opportunity to contribute to their maximum capability, regardless of background, work style, or location.

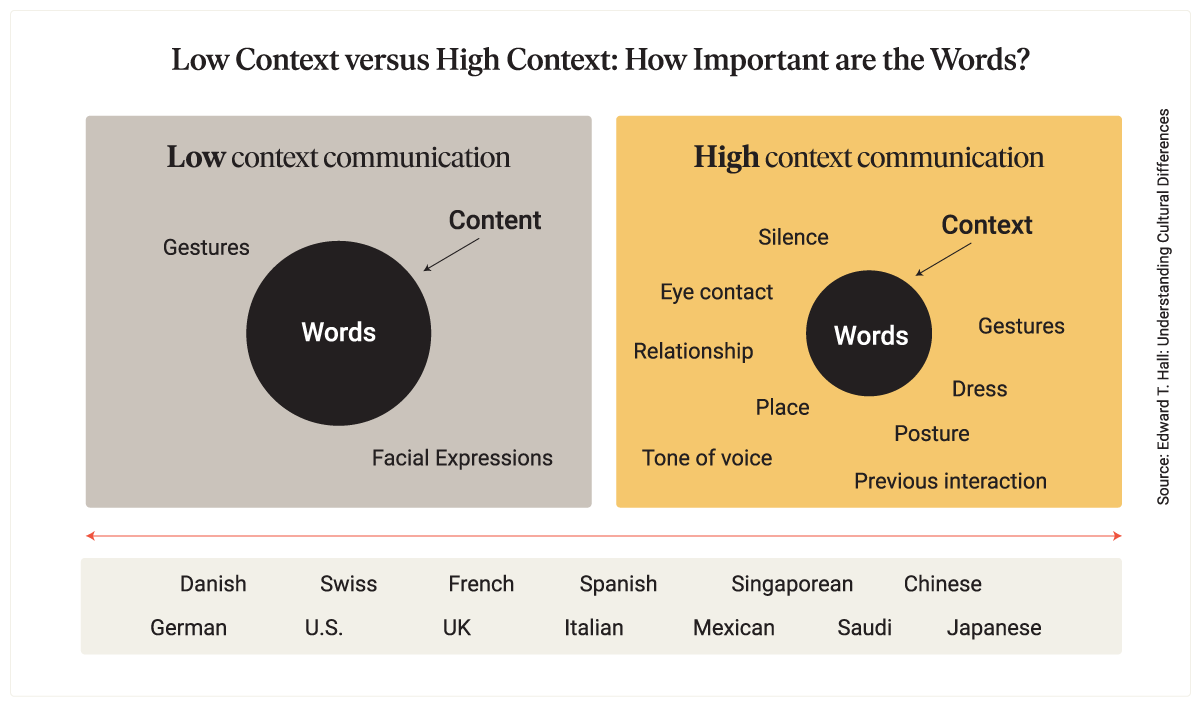

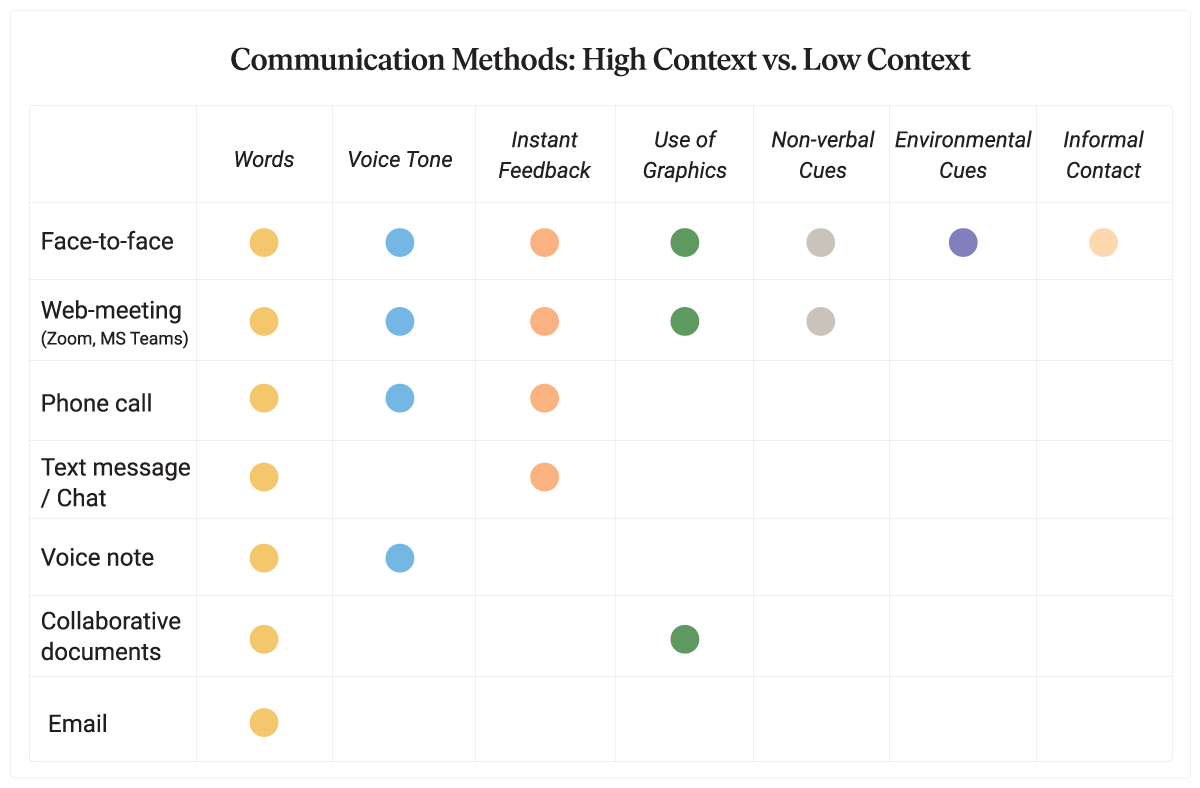

When communication occurs across distance and time zones, messages often fail to convey crucial context, and misunderstandings easily occur. It is important to consider the role of context in communication, and ways that messages in a hybrid team setting may lack context and give rise to mistaken interpretations. The same verbal message—say, “You’ve done a good job so far”—could be understood very differently in a direct, literal, low-context format, compared with a more indirect high-context environment where other information is readily available, such as a manager’s tone of voice or facial expression.

Team members communicating virtually should take special care to provide additional context for messages that could be misunderstood or give rise to conflict. This could mean walking through a message in a virtual meeting rather than just sending an email, or responding to a chat message with a phone conversation. Email is one of the lowest context forms of communication, and is generally not the best method for addressing conflicts.

How can you make everyone feel like an insider? Employees who are remote from headquarters as well as from the team leader often feel they are missing out on information and relationship-building with other team members, and that they are neglected when it comes to career development opportunities. “Proximity bias,” or the natural tendency for people to pay the most attention to those who are located nearby, may reinforce this sense of missing out, as team leaders appear to focus on colleagues who are co-located or from the same part of the world. Team leaders can avoid unintentional acts of exclusion while expanding the team “in-group” in a variety of ways that foster creative interaction and alignment:

We’ve collected data from more than 2,000 teams—one of the largest available sources of information anywhere regarding the performance challenges encountered by global teams. Our survey data strongly supports the need to not only establish a firm foundation for any global team, but also to reinforce this foundation consistently over the team’s lifespan. The 14,000+ team members we surveyed rated three items as being most critical overall:

In multicultural, hybrid, or virtual teams, it can be difficult to establish and maintain a common set of goals. Team members are likely to ask more than once, for instance, “How do these goals apply in my region?” and to seek greater clarity about their roles and responsibilities if these differ from assignments given by their local manager. Ongoing attention and reinforcement is necessary to ensure clarity and commitment to goals and roles. Additionally, trust-building is never just a task to check off a list, but a continuous effort in order to help diverse teams thrive.

There are steep challenges involved with both diverging to generate new ideas and converging to create a plan and get things done together. However, multicultural teams at their best bring together a wider array of perspectives and expertise to accelerate growth in new markets and global economies of scale while cultivating rising leadership talent.

—

Download our latest white paper, What’s Different about Multicultural Teams? From Divergence to Convergence, to learn even more about supporting your global teams, and start a free trial of the Aperian learning platform to see how it can help your organization succeed.